Posted by Amber Williams on 18th Jan 2022

The Flower Girls of London

19th century London, as history recalls, was a tough ride for most, regardless of whether you were rich or poor. Many people went hungry, cold, and worked tirelessly for their money.Due to a myriad of reasons, whether it was due to losing loved ones from disease or just a lack of income, hundreds (if not, thousands) of children became orphans at a young age.

With living conditions the way they were, children as young as five had to find themselves work. Stall merchants and street sellers were a common sight on the cobbled streets of our capital. Among them, you could find both children and adults selling seasonal flowers from baskets. They were known as the ‘London flower girls’, and this is where our story begins.

Fear

of the Workhouse

The workhouse. A word that struck fear into the hearts of the working class.

People dreaded these bleak and overcrowded institutions and did all they could

to avoid them. From 1834, paupers would be sent to workhouses, giving them

accommodation in exchange for gruelling work and subpar conditions.

Before this, those in need were looked after via money that was collected by the wealthy. After The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, the poor could no longer receive this relief unless they lived in workhouses and performed tedious tasks and jobs daily.

Workhouses existed long before this amendment was passed, but Rev. John Becher set the standard for the notorious workhouse and its conditions. Building his very own institution in 1834, it’s said that he wanted the workhouse to emulate prisons, both in its decor and daily regimes.

Becher made no secret of his love for social reform. His intentions for his workhouse became legendary, setting the standard for the rest of the country’s institutions.

Actively supporting segregation and strictness in his workhouses, Becher believed that if you make living conditions unbearable, people will work harder to avoid them.

He had exceptions to his rulings, particularly for those who he deemed ‘blameless’. This applied to people who were either too old to look after themselves or too ill to work. For everyone else, workhouses weren’t very pleasant, and many people lost their way once admitted to these institutions.

Whilst living in workhouses, it was common for families to be separated. Parents would be given jobs within the workhouse, carrying out remedial tasks like cracking stones, whereas children could be sold to different industries.

Child

Labour in Victorian England

Until 1879, most working-class children didn’t go to school. Kids as young as 4

or 5 could be found working in mines, mills, and factories, helping their

families to buy food and pay for lodging. Usually, boys would be encouraged to

enter a trade as an apprentice, whereas girls would become servants or factory

workers.

As children started work, they would be given jobs that the average adult couldn’t. For example, young boys would work in mines as they could fit into small, enclosed spaces. As you can imagine, many of these jobs were unsafe, and hundreds of kids would get injured on the job.

From sweeping chimneys to making matches, children of the industrial age had very little time to be kids, to play, to have fun with their siblings or friends. The main concern for the working class was simply to stay out of workhouses and put food on the table for their families.

London's

Flower Girls

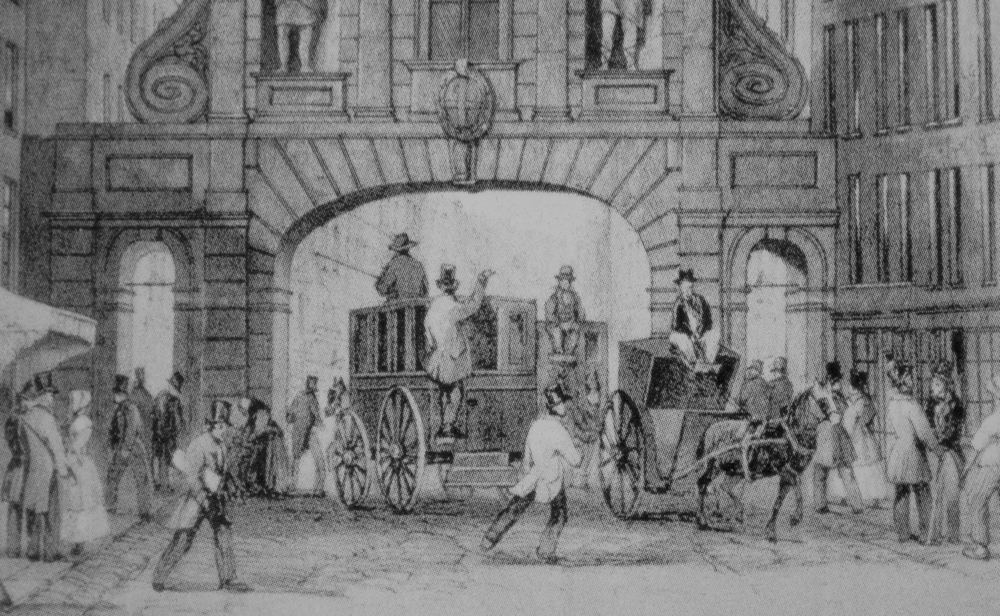

It was quite common to see people selling various goods or services on the

streets of large cities. Street sellers, or ‘costermongers’, could be found

flogging literally anything you can think of, whether it be fish, soup,

clothes, drinks, homemade items, or even flowers.

You couldn’t go a place in London without coming across several flower merchants. As they were often sold by young girls and women, they became known as the London Flower Girls.

According to the word of Henry Mayhew’s ‘London Labour & London Poor’ (published 1851), there were two types of flower girls. Those who were in their teenage years and early twenties and had, apparently, fewer ‘pure’ intentions, would sell their goods late into the night. The other half of the coin would be much younger children, helping their families or themselves by selling their seasonal picks.

“Sunday is the best day for flowerselling, and one experienced man computed, that in the height and pride of the summer four hundred children were selling flowers on Sundays in the streets.”

From roses and pansies to daffodils and primroses, these girls sold anything they could get their hands on and sold them well.

Fifteen years before Mayhew’s publication was released, flower girls weren’t as common a sighting on the cobbled roads of our cities. If people wanted flowers, they would have had to go to markets or nurseries, and the prices were much dearer. This also meant the poorest of classes found it difficult to afford their favourite blooms, so once the flower girls came along in their abundance, the working class leapt at their cheap prices per bunch.

Hundreds of child street-sellers were orphans. They would prepare their bunches themselves at the crack of dawn before people started their morning commutes. People believed that it was rare to come across a flower girl that wasn’t Irish. According to Toilers in London; or Inquiries concerning Female Labour in the Metropolis, [Anon] 1889, they would leave their homes searching for a better life but found themselves selling watercress and violets on the streets.

It’s easy to picture these young women, running around the streets of London, selling their hand-prepared bunches of flowers to passersby. Henry Mayhew describes their selling technique in his written work as a harsh pester.

“They are generally very persevering, more especially the younger children, who will run along barefooted, with their, “Please, gentleman, do buy my flowers. Poor little girl!” or “Please kind lady, buy my violets. O, do! please! Poor little girl! Do buy a bunch, please, kind lady!”

Thomas

and John’s Rescue

As the industrial age roared on and Queen Victoria’s reign came to an end in

1901, children weren’t seen selling on the streets as much as before. This was

influenced by several factors. By 1890, several acts were passed making it a

legal requirement for children in workhouses and factories to be given six half

days of school per week. Eventually, this was amended, and the government gave

school boards funding, allowing them to accept children of poorer status.

Then came Dr Thomas Barnardo and John Groom. Barnardo felt that workhouses were a poor environment for children and made it his mission to create proper children’s homes, helping thousands of orphans and those from poor families. He then later went on to create the self-named charity, Barnardo’s, which we know is still up and running to this day.

In 1866, John Groom founded the ‘Water Cress & Flower Girls’ Christian Mission’, or what later was known as ‘John Grooms Crippleage’.

His mission outlined that he wanted to provide the flower girls with mugs of hot cocoa every morning and a hot dinner in the evening. There were also facilities for washing and mending clothes, helping the girls stay warm, dry and clean. In 1876, the crippleage moved to larger premises that included a schoolroom, holding around 350 students and a soup kitchen. The crippleage then became a floristry factory, where many of the girls worked.

Donations to

the charity helped to house children that worked there and allowed them to hire

‘house mothers’ who looked after the girls at their accommodation.

The Future of Flowers

With flowers now much more affordable to the average person, and easily accessed, people started to grow their own from seeds and bulbs in gardens and allotments. Eventually, the rise of the Netherland’s flower market overtook most countries, providing us with both cut flowers for florists and bulbs for wholesalers and retailers.

Although the flower industry has changed dramatically throughout history, we still remember the London Flower Girls and the love they had for their craft, whether it be from the art of selling or simply being near sweetly fragranced flowers each day.